In Europe, towards the end of the nineteenth century, modern design movements emerged in Scotland, Austria, Germany, and France, responding to the effects of mass production and the degradation of historical styles. The output and philosophies of designers exploring new modes were diverse. Some focused on luxurious craft production for a wealthy clientele, while others sought to unite craft with manufacturing. In general, the designers abandoned historical precedents and endeavored to create a new style appropriate to the modern age. Their works commonly rejected applied ornament in favor of flat, simplified decoration and drew heavily on geometric forms and foreign cultures for inspiration.

Elaine Wormser’s bedroom demonstrates the synthesis of these various influences in American design. The rigid, rectilinear forms of the nightstand and bookcases draw upon the austere geometric grids of Viennese designer Josef Hoffmann and the shapes of American skyscrapers. The neoclassical proportions and undulating curves of the desk, headboard, and occasional tables, meanwhile, embrace the sumptuous moderne forms of French designer Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann.

The Wiener Werkstätte

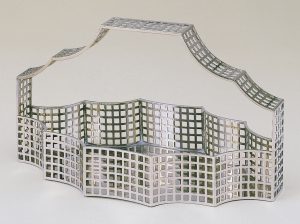

The Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop), an artistic cooperative formed in Vienna by Josef Hoffmann in 1903, influenced many modern American designers. The Werkstätte gave contemporary expression to the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement, emphasizing a return to craft production, the unity of fine and applied arts, and a belief in the power of design to restore beauty and vitality to everyday life. These notions were embodied by the concept of the gesamtkunstwerk (a total work of art), in which a project’s various forms and individual elements were designed as a coherent and harmonious whole. Those who subscribed to such a comprehensive approach, like Joseph Urban, were uniquely equipped to create across a broad spectrum of media.

The Werkstätte’s influence reached America directly through Austrian immigrants like Urban. In 1922, he opened the Wiener Werkstätte of America showroom in New York. A critical success, it was a financial disaster, closing after only a year and a half of operations. It is possible that some of the objects in Elaine’s bedroom, such as the ceramic head created by Vally Wieselthier, originated from the showroom’s inventory.

French Moderne and the 1925 Exposition

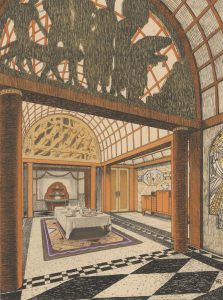

After the devastation of World War I, France revitalized its design industries as an expression of national pride and economic recovery. In 1925, the new style moderne was unveiled to an international audience at the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes in Paris. Over 20 countries were invited to submit displays to the exposition, on the condition that all objects shown were of original and modern design. The presentations of French manufacturers dominated the fair, featuring stylized ornament, rich materials, and works of technological sophistication. Yet rather than turn away from the past completely, many designers fused neoclassical forms with contemporary sources of inspiration: Cubism, De Stijl, the arts of Africa, Japan, Aztec Mexico, and ancient Egypt and sleek forms inspired by the modern city.

We do not know whether the Wormsers visited the 1925 exposition in Paris. However, they could have seen an exhibition of nearly 400 objects selected from the fair that traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1926. Wealthy Americans encountered modern French designs (or echoes of them) through department store showrooms, as well as travels across the Atlantic on luxury liners bedecked in modern décor. Sailing to Paris on the SS Île de France, the first ship to feature interiors in the spirit of the 1925 exposition, the Wormser family had ample opportunity to admire spaces designed by the style moderne’s most prominent figures.