Urban played an integral role in introducing modernism to America and in showing Americans the possibilities of the new style—how it could be used as they fashioned themselves and their spaces. He did this through an astonishing range of creative work: designing opera, theater and film sets, buildings, interior spaces, textiles, and products ranging from furniture to cars.

Opera and Theater

Urban came to the United States in 1911 to serve as art director of the Boston Opera. There, he introduced Americans to modern European stagecraft, which relied on the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk: the creation of a ‘total work of art.’ (Urban would later apply this concept to all of his projects, including the Wormser Bedroom.) This approach depended on the harmonious synthesis of all artistic elements: setting, costumes, lighting, stage movement, and sound—something that is so commonplace today that it is hard to imagine a time when this was not the norm.

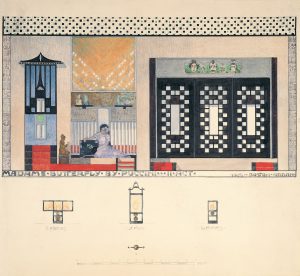

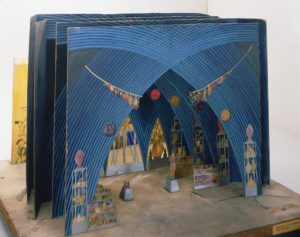

Note Urban’s sketch of the interior of Madame Butterfly’s house. The pure, modern geometry and colors of the set and the character’s costume all work together to create a cohesive, transportive illusion of a distinct time, place and atmosphere. Astonishing and revolutionary, Urban’s sets often received applause as a new scene was revealed.

After the Boston Opera was shuttered in 1914, Urban worked for New York’s Metropolitan Opera. Here, his creations drew the attention and praise of an even larger audience. From 1917 to his death in 1933, he created designs for more than fifty Met productions and directed his studio workshop, which built the scenery and oversaw installation and lighting.

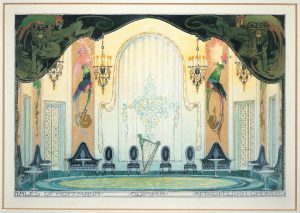

Many of the devices and forms that Urban used for operatic and theater sets were also used in his work in other modes, including Elaine Wormser’s bedroom. Notice how the curve of the sofa backs in his sketch for The Tales of Hoffmann are echoed in the headboard of Elaine’s bed.

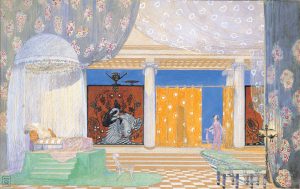

In this sketch for La Belle Hélène, Urban frames areas of the stage for the viewer to focus on using curtains and a stepped platform (or stage) for the bed. He would later use similar framing devices in the Wormser Bedroom.

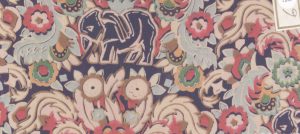

Urban’s dripping florals in the 1920 set design for Parsifal materialize later in the decorative motif he designed for the wall curtains that appear behind Elaine Wormser’s bed.

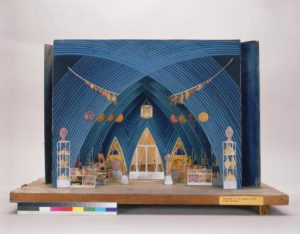

After studying the libretto for an opera or the script for a theatrical production, Urban would create sketches of his set designs. From these, miniature scaled models were created. Models were typically one to two feet high, up to three feet wide and from eight inches to two feet deep. Outfitted with their own lighting systems and moveable parts, the models were used to confirm light direction, angles of visibility from all parts of the theater, scale, overall concept and stage management details. Over 300 of these carefully crafted models are preserved at Columbia University.

SEE: More of Urban’s set modelsZiegfeld Follies

Featuring beautiful young girls in elaborate costumes performing choreographed production numbers to music by Irving Berlin and George Gershwin, the Ziegfeld Follies became a symbol of the 1920s. The Follies were started by Florez Ziegfeld in 1907 and modeled after the Paris Folies Bergère. Each year, a new edition of the revue debuted on Broadway in New York, then toured various cities, including Chicago (Ziegfeld’s hometown).

In 1915, Ziegfeld hired Joseph Urban to bring a new sophistication to his productions. Though some people chided Urban for becoming involved in such “frivolous entertainment,” Urban understood the power of the popular and widely viewed show and its potential to introduce his talent and design ideals to the masses. Each edition featured as many as twenty numbers and required about twelve full stage sets. Urban created these for every edition through 1931.

WATCH: Scenes from Glorifying The American Girl to see Joseph Urban and Ziegfeld Follies performers.

Black and white video of Joseph Urban in a suit walking among a crowd of people and talking to two young women; color video of young white women in skimpy, translucent costumes with elaborate headdresses descending a set of stairs on a dramatically lit, Urban-designed set with a dark painted backdrop.

Joseph Urban entering a performance and “There Must Be Someone Waiting For Me,” Technicolor finale from in Glorifying The American Girl (1929)

Film

In 1920, Joseph Urban became art director for William Randolph Hearst’s Cosmopolitan Pictures. This new pursuit placed Urban’s set designs before the eyes of millions across the country. By 1929, American movie theaters averaged 80 million visitors per week. Enthusiastic about the prospects of the medium, Urban remarked, “The motion picture offers incomparably the greatest field to any artist of brush or blueprint today. It is the art of the twentieth century and perhaps the greatest art of modern times. It is all so young, so fresh, so untried.”

When possible, Urban injected his sets with the modernist style. Film critics cite his sets for “Enchantment” (1921) as the first to incorporate modern décor in American film. Urban’s furnishings and patterns in both “Enchantment” and other films like “The Wild Goose” pay homage to the modern Viennese style associated with the Wiener Werkstätte and championed by Urban.

WATCH: Scenes from “Enchantment” (1921)

Series of black and white film clips showing the following scenes: A young white woman sitting at a shiny black desk in an interior decorated with translucent drapes and hanging lamps with cylindrical, transparent glass shades; a man and a woman eating in a dining room featuring black cabinets with white detailing and a central cluster of hanging lamps with cylindrical, transparent glass shades; two white men sitting in a restaurant decorated with conical, black and white hanging lamps and black and white wallpaper composed of large rectangles and geometric flowers; people dancing in a ballroom with black and white gridded wallpaper; three men and a woman sitting down in a restaurant decorated with conical, black and white hanging lamps and black and white wallpaper composed of large rectangles and geometric flowers; a group of people sitting in curved-back chairs in a large room with transparent drapery in a triangle pattern; a woman dressed as a princess and five children playing ring-around-the-rosy on a stage set with three large circular alcoves and a canopy curtain hanging over a bed at center stage.

A variation of Urban’s design for Elaine Wormser’s occasional table appeared in “Doctors’ Wives” (1931), starring Joan Bennett and Warner Baxter. Urban was hired to design the sets for this Fox film.

Architecture and Interior Design

In an act of disobedience, the young Joseph Urban used the tuition money his father gave him to attend law school to take art courses. After this discovery and much heated discussion, Urban’s father agreed that his son could study architecture. Urban pursued this training at Vienna’s Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied with the influential modern architect Otto Wagner.

Urban became licensed to practice architecture in the United States in 1926. Using earnings from his film and stage work, he established his Manhattan architectural office. From there, he designed homes, buildings and spaces in New York and beyond in a range of styles. Architecture presented the opportunity for Urban to leave a more permanent mark, unlike his ephemeral stage creations.

Urban tackled this work with the same Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) approach that he applied to all his projects. In addition to creating the structure or framework for a project, Urban wrote, “I do all the decorating and ornamentation myself. Frequently I select the furniture and the fittings, personally, and I should even like to choose not only the people who live in my houses, but the clothes they wear and the things they do. Then I would be certain to exclude all jarring notes.”

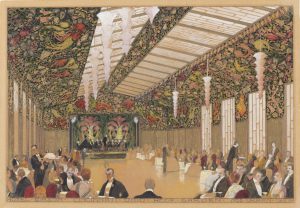

Elaine Wormser recalled that her father met Urban through his work on the Central Park Casino. Urban’s design for the casino’s ballroom, which opened in June 1929, and the Wormser Bedroom, completed in the summer of 1930, shared a similar color palette of black, green and gold. Both projects featured black woodwork and black glass. As Urban used black glass on the walls of the Wormser Bedroom to create the illusion of more space, he used black glass on the casinos’ ceiling to make the room feel as if it had higher ceilings.

SEE: Urban’s decoration for the New Amsterdam Roof Garden in New York

Black and white video of a line of chorus girls kicking their legs in unison inside of an interior designed by Joseph Urban, with a floral wall mural and ceiling lights with conical black and white shades.

Urban’s decorations for the New Amsterdam Roof Garden in New York, featured during a Ziegfeld Follies performance.

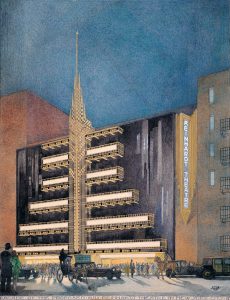

Urban’s New School for Social Research in New York (1930) is heralded as one of the earliest examples of the International Style of architecture in the United States. Note the linear clarity of its façade. Reflecting on its importance, Gretl Urban eloquently and accurately stated, “it was a building of the future for the future.”

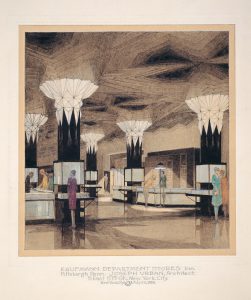

Urban’s designs for the New School’s interiors demonstrated his mastery as a colorist. This study for the school’s dance studio reflects the energy and spatial rhythm that Urban could achieve with color. Note how bold, syncopated colors seen here recall the striped upholstery fabric Urban designed for the Wormser Bedroom.

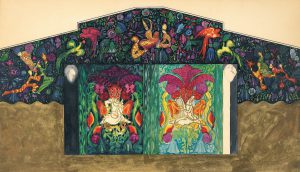

Urban designed a new roof garden for Cincinnati’s Hotel Gibson at Walnut and Fifth Street in 1928. For this, he created a brightly colored stage and wall murals with flora and fauna in what the newspapers described as a “futuristic style”, new lighting schemes and modern furniture. In the roof garden’s lobby, Urban covered the upper walls and ceiling with silvered leather, much like he gave a silvery effect to the Wormser Bedroom ceiling by using aluminum gilding.

In 1926, Urban was asked to create the interior decoration for Mar-a-Lago, the Palm Beach estate built for businesswoman and socialite Marjorie Merriweather Post. The artist created this egg-domed bedroom for her daughter Nedenia. Born in 1923, Nedenia was much younger than the teenaged Elaine Wormser when Urban designed her bedroom. He created audacious, bespoke backdrops tailored to the age of each girl. Though very different in character, each room combined organic floral designs with sleek modern elements. In Nedenia’s bedroom, the painted roses trailing up the walls are juxtaposed with modern light fixtures and black and gold avant-garde furniture carved by Urban’s Viennese friend Franz Barwig.

Product Design

In a 1930 newspaper article headlined “Excels Because He Does Not Specialize,” Urban spoke about the range of his work, spanning from buildings, furnishings, and film sets to automobiles, luggage and silks:

“I find that a rotation of jobs, like a rotation of crops, aids fertility…. If I tire of one type of problem, I can turn to another and come to it later, refreshed and eager. There is nothing phenomenal in my ability to do all these different things. They all, more or less, require planning, sketching, decorating and an artistic turn of mind. I may have carried my artistic ability further afield than most artists, but that is because I believe there is room for artistic detail as well as utility in practically every commodity that is produced.”

To Urban, it was critical that spaces and products, no matter how seemingly inconsequential, should be adapted and designed to reflect the new, modern mode of life.

Manufacturers of the Ruxton motor car tapped Urban to create a special color scheme for their cutting-edge vehicle. Urban created an exterior color scheme of horizontal stripes with graduating tones to emphasize the car’s low clearance and elegant, attenuated body design. Multiple colors of blue, mahogany brown and, by some accounts, green, were used on the roof and fenders, and six horizontal bands of color ran along the sides of the car. Urban’s role as color designer for the automobile was prominently featured in Ruxton’s advertisements.

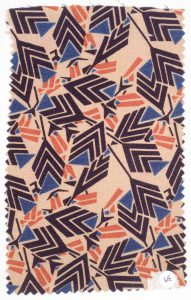

Urban also designed the striped upholstery fabric for the interior of the Ruxton sedan. Titled “Rigato Ombre,” it was produced by F. Schumacher & Company of New York. Aside from its color palette, this striped moiré, or watermarked, pattern is similar in design to the fabric that Urban created and used to cover the Wormser Bedroom’s armchair, dressing table chair and daybed.

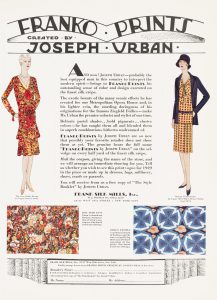

In 1928, Joseph Urban was engaged by Frank Silk Mills to create designs for printed silks. In advertisements for these so-called Franko Prints, Urban was noted as “the best equipped man in history to interpret the modern spirit,” and “the premier colorist and stylists of our time.” Sold far and wide, these silks were used to make dramatic modern dresses, handbags, shoes, draperies and pillows. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York holds over 40 samples from Urban’s Franko Print series. This collection attests to the vivid and imaginative range of colors, moods and motifs that Urban produced for the project.

The Wiener Werkstätte of America Showroom

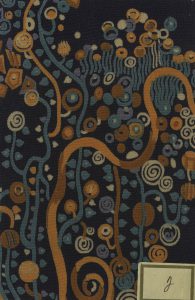

In July 1922, Joseph Urban opened the first Wiener Werkstätte showroom in America at 581 Fifth Avenue in New York City. The Wiener Werkstätte (Vienna Workshop) was a collaboration of artists established in 1903 and led by architect and designer Josef Hoffmann. Striving to create works that reflected the modern era, they created designs ranging from ceramics, fashion, and silver to furniture and the graphic arts. These works exhibited a range of aesthetics, but most importantly, they looked forward, rather than back to historical precedents. Urban’s influential Wiener Werkstätte showroom played a key role in introducing Viennese modernism to American audiences and designers.

Holding true to the importance of creating a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), Urban created an immersive experience for visitors to the New York showroom. Organizing the space into a series of rooms, complete with floor and wall treatments and furniture—most of his own design—he illustrated how the Werkstätte’s modern works could be incorporated into a home. In addition to pieces by Werkstätte designers, Urban exhibited paintings by Austrian modernists Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele.

Intrigue about these fresh Viennese designs was high when Urban opened the showroom, but sales never really took off. Forced to close the enterprise in just over a year, Urban lost most of his investment and nearly went bankrupt. Some attribute the failure of Urban’s venture to it being ahead of its time—most Americans weren’t ready to bring modernism into their home. Others cite the downturn of the economy in 1920 and 1921, or the anti-German sentiments that lingered after World War I.