From the mid-nineteenth century onwards, women’s opportunities for education and employment expanded steadily though unequally. By the 1920s, the increased availability of consumer goods and the rise of film and radio produced a popular culture that celebrated and, at the same time, undermined the independent, educated, and sexually expressive young woman. She was encouraged to be savvy, confident, and outgoing, but only to the extent that she remained attractive and unthreatening to men. Everywhere she turned, Elaine Wormser would have encountered conflicting depictions of the “modern girl” in films, advertisements, and life. Perhaps, gazing at her reflection in the polished glass walls of her modern bedroom, she considered these conflicting ideas as they related to the woman that she was becoming.

The Age of the Flapper

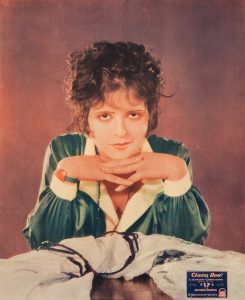

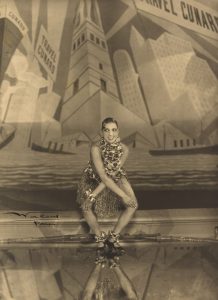

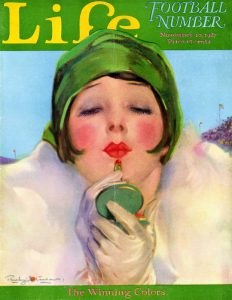

Who was the flapper? During the 1920s, “flapper” generally referred to the young, middle-class women living in cities who rejected traditional expectations for their gender and embraced consumer culture. Perhaps more of a commercial icon than a lived reality, the flapper was ubiquitous in advertisements, films, literature, and magazines—particularly in media that targeted young women like Elaine. Although images of the flapper often depicted a young, slender, infinitely chic white woman, the behaviors and modern styles associated with the flapper crossed racial and class lines. In depictions and real life, flappers smoked, drank, bobbed their hair, wore makeup, drove cars, danced to jazz music, and socialized casually with men. Mainstream society regarded their behavior as degenerate, but also as indelibly modern.

WATCH: A flapper doing the Charleston.

Black and white video of a young white woman wearing a cloche and a dress with a raised hemline performing a dance involving swinging her arms back and forth and shuffling her feet. A band of young Black boys in dark uniforms play horn instruments behind her, while one boy does the Charleston alongside the woman.

Miss Bee Jackson dances the “Charleston” while the Jenkins Orphanage Band plays in the background in Charleston, North Carolina, 1926. Fox Movietone News Collection, Moving Image Research Collections, University of South Carolina. Music by Ted Lewis and His Band, “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” Columbia (1084-D), 1927.

The Rise of Cosmetics

Sitting at her dressing table, Elaine might have applied a skin cream sold to her by a friendly saleswoman at a department store counter. Next, a face powder she’d seen in a magazine advertisement featuring a sultry film star. Her perfumes sat in bottles created by famous French designers, their packaging calibrated to whet a shopper’s appetite for glamour.

Makeup was once stigmatized as a form of feminine deceit. However, by the 1920s, cosmetics had ballooned into a lucrative industry. Surrounded by popular images of beauty in films and magazines, and highly attuned to their own visibility in public, many young women in the 1920s turned to cosmetics as both an act of self-fashioning and a way to meet heightened expectations for beauty. Advertisements plied women with products for clear, youthful skin, alluring eyes, and slim figures. No longer a challenge to feminine respectability, cosmetics now shaped feminine norms and tied women’s self-expression closely to consumption.

Women in Higher Education

In 1930, as her bedroom was completed, Elaine Wormser enrolled at the all-women’s Pine Manor Junior College in Massachusetts. Doing so was exceptional among the general American population, but common for her social class. Women’s college enrollment increased steadily throughout the early twentieth century, along with the number of women entering professions such as law, medicine, and science. By the 1920s, attending college was generally viewed as an acceptable, but not serious pursuit for white, mostly middle-class women—although women of all racial backgrounds enrolled in college in this period. If they pursued a career, women graduates during the ‘20s were frequently limited to low paying vocations such as teaching, nursing, and social work. Perhaps due to a combination of social pressures and genuine romance, many white female graduates like Elaine married shortly after college rather than entering the workforce.

The Right to Vote

Decades of work by suffragists culminated with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920: Women—or at least those recognized as U.S. citizens—were now guaranteed the right to vote. Young women like Elaine were empowered with the knowledge that they could exercise their political voice, if they chose to. Yet many other women, including Native Americans, Asian American immigrants, and Black women, remained obstructed from voting by citizenship requirements or voter suppression tactics.

Women in the Workforce

Women in urban areas made gains in manufacturing and white-collar work after World War I, accounting for one in five wage earners by 1927. White American-born women could enter clerical roles, while European immigrants like the Wormser’s three live-in staff were able to leave domestic service for positions as factory workers and shop girls. Yet even as a belief in the new, politically and socially emancipated woman pervaded the era, many women found little improvement in their material realities. Across occupations, women’s wages remained inferior to those earned by men, with minimal opportunity for professional advancement. Progress was also uneven: most Black, Mexican American, and Asian American female wage-earners found themselves excluded from the newly available roles, and remained limited to domestic service and agricultural work.

WATCH: Women work at a cigar factory in Tampa, Florida in 1930.

Black and white video of three young women with bobbed hair sorting and stripping tobacco leaves by hand as a man reads a newspaper in Spanish in the background.

Cigar factory workers, Tampa, Florida, 1930. Fox Movietone News Collection, Moving Image Research Collections, University of South Carolina.