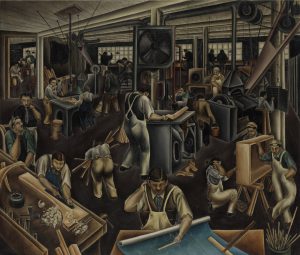

From sheet glass to synthetic textile dyes to colorful plastics, the labor of industrial workers supplied nearly every detail of Elaine’s bedroom. These workers, aided by mechanized tools and regimented by mass production techniques, toiled long hours for low wages in unsafe conditions.

Many industrial workers were impoverished Eastern and Southern European immigrants and their children, who arrived in American cities between 1880 and the early 1920s. By the end of the 1920s, a growing number of factory workers were Black migrants from the American South, who sought better jobs and social protections in northern cities and steel towns. Although a lack of documentation prevents us from knowing the particulars of many workers’ lives, these individuals played an equally important role in the development of American modernist design.

The fourteen men employed by Mallin Furniture Company in 1929 likely emigrated from Eastern and Southern Europe. Depending on their specialization, they were paid between 30 and 90 cents an hour. (A female worker would typically be paid half this amount.) After working a fifty-hour week operating machinery, sanding wood, or applying finishes, the workers would return to a cramped room in one of New York’s overcrowded tenement houses. There, they raised their children, socialized with neighbors, and perhaps enjoyed one of the leisure activities afforded by the modern age.