When Elaine’s room was finished in 1930, the Wormsers employed three live-in domestic workers: Ina Alam, a 33-year-old Scottish woman who immigrated in 1929; Edith M. Thulim, a 23-year-old Swedish woman who immigrated in 1923; and Amelia Thoridl, a 44-year-old German woman who arrived in 1906. While there is little documentation of these women’s lives, their stories are no less important to consider. Based on census records, we know that Ina and Amelia were employed as maids, while Edith, the youngest, served as a cook. The three women were an essential part of the Wormser household: they cooked, cleaned, and maintained the beauty of the apartment’s furnishings and decorations.

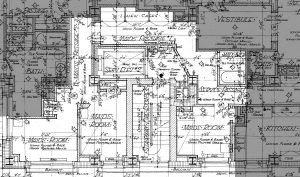

Ina, Amelia, and Edith lived in maid’s quarters on the east side of the apartment, with separate passages and elevators and a small, shared bathroom. Their rooms and the kitchen, where they likely spent their downtime, had views of Chicago’s cityscape. Based on accounts from workers in other households, we can assume that the women’s lives were in many ways quite isolated. As one household worker wrote in 1915, “There is no place where one is more lonely than to be alone with people, and that is what working in a house means to so many, though not all.”

Domestic Service in the Early Twentieth Century

Once regarded as essential for middle- and upper-class households, domestic service in the early twentieth century was notoriously difficult and degrading work performed by working class women. The hours were long, the duties were arduous, and personal freedom was severely limited. Many women preferred jobs in factories, shops, and even laundries.

As employment opportunities expanded for American-born white women after World War I, domestic work was increasingly the vocation of those systemically excluded from better roles. In cities like Chicago, Black women migrating from the South had little choice but to enter the domestic service industry, where they precipitated a shift away from live-in domestic work. For white women, including many immigrants, work was a temporary stage in their lives that concluded upon marriage. For Black women, however, domestic work was often a lifelong occupation due to racial discrimination, which unfairly limited job opportunities and depressed wages.

The dwindling labor supply and growing middle-class dependency on Black, often married, household workers enabled these women to set some of the terms of their employment. Their preference for living with their own families and desire for control over their work hours engendered a trend towards “day work” during the 1920s. At the same time, new domestic technologies and the growing popularity of apartments and smaller homes among the middle-class reduced the number of chores, minimizing the need for around-the-clock domestic service.

Among upper-class households, live-in work still prevailed as both a matter of convenience and a symbol of wealth. Although many women preferred the relative freedom gained by living outside their employer’s home, live-in work with an affluent family appealed to some European immigrant women as a stable place to live and a way to acculturate to their new environment.

Yet live-in work had many drawbacks. For instance, Amelia, who was married, would have lived apart from her husband throughout her employment. Due to language barriers and a lack of formal education, Edith, Amelia, and Ina would have faced limited options when they arrived in the United States. However, hailing from the so-called “desirable” regions of northern and western Europe gave them a distinct advantage in the job market, likely enabling them to secure higher-paying positions in an upper-class home.